Regina coeli laetare, Alleluia.|

Quia quem meruisti portare, Alleluia.

Resurrexit sicut dixit, Alleluia.

Ora pro nobis Deum. Alleluia.

Rejoice, Queen of Heaven, alleluia.|

For he, who you were worthy to bear, alleluia.

Is risen, as he said, alleluia.

Pray for us to God, alleluia.

The Regina Caeli is one of the four seasonal Marian Antiphons sung after Compline (the night office) during the liturgical year. We have recorded two of the antiphons for the Music in Isolation series during the pandemic, the Alma Redemptoris Mater, used from Advent through the Feast of the Presentation on February 2, and Regina Caeli used for the Easter Season. The other two, Ave Regina Caelorum sung from Presentation through the Wednesday of Holy Week, and the Salve Regina sung from Trinity until the end of Ordinary Time, have been featured on several Polyhymnia concerts over the years. These four are the last remaining Marian Antiphons, survivors of a Pre-Counter-Reformation collection of elaborate texts, best represented today by the Eton Choirbook. While all of the other three whose meditative texts have been beautifully rendered by numerous composers throughout history, it is the Regina Caeli that holds particular importance in the time of pandemic in which we find ourselves.

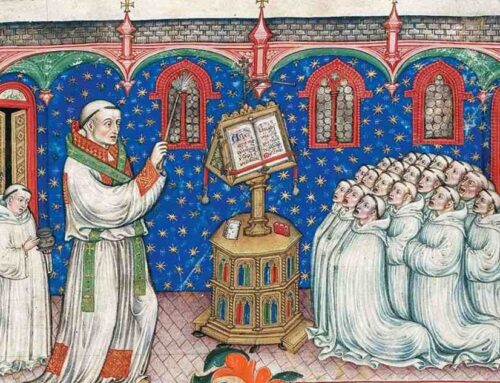

In about 1260, Jacobus de Varagine wrote a collection of hagiographies or biographies of saints and other liturgical figures called the Legenda Aurea or Golden Legend. It is proper medieval writing, mostly legend, and all of it colorfully written. But it is the story about the Regina Caeli and Gregory the Great (Pope from 590-605) that is of interest here. In 590, the plague was ravaging Rome, and special liturgical intercession was called for. Varagine describes a massive liturgical procession in which an image of the Virgin Mary was carried through the streets of Rome. Then, suddenly, angels were heard from above singing the first three petitions of the Regina Caeli. (Regina coeli laetare, Alleluia. Quia quem meruisti portare, Alleluia.Resurrexit sicut dixit, Alleluia.) After hearing the angels, Gregory the Great added the fourth verse: Ora pro nobis Deum, Alleluia after seeing a vision of the St. Michael the Archangel, sheathing his sword on top of Hadrian’s Tomb, known today as the Castel Sant’Angelo, signifying the withdrawal of the plague.

So, it seems that the Regina Caeli, as our most recent choice for the Music in Isolation series, is perhaps a bit more than seasonal. The image of St. Michael sheathing his sword, and in particular the image of the sword, has been speaking to me a lot lately. Throughout history, the image of the sword has been interpreted as a weapon of aggression, a symbol of office, and a sign of fealty or capitulation. It can also be seen symbolically as an instrument of healing; Excalibur from the Arthur legend comes to mind. Or, from a more personal perspective, through the injection of the life-saving vaccine. In a sense, when the nurse who was a complete angel, by the way, had given me my shot, she sheathed her sword, and like the legend of St. Michael so may centuries earlier also signified the withdrawal of a pestilence. Do I believe the legends at their face value? My head says no, but my soul is not so convinced. Either way, I love legends. What I do believe is that legends have great power. They survive for a reason. If not, then explain the modern-day fascination with the King Arthur story. Arthur is an enduring story based on a legend, based on a myth. From Gildas the Wise (c. 500) to Geoffrey of Monmouth and Chrétien de Troyes (12th Century), to John Dryden’s somewhat “out of left field” take for Henry Purcell’s semi-opera in 1691, and ultimately to Hollywood. In the end, Varagine and other medieval writers of hagiographies were creating their legends to supplement biblical legends, in which miracles abound, for a society where directed divine intervention was noticeably less frequent and often replaced by hopelessness and despair. These colorful and comforting accounts were especially needed during the relentless visitations of the plague throughout the centuries. Each time the plague arrived, new stories were written, and eventually, new legends were created.

Polyhymnia is a secular organization, though I am a practicing Christian and a high-church one at that. Regardless of your faith or none, the music that Polyhymnia performs is inarguably beautiful and reflects the genius of the composers who wrote it. People flock to see the Leonardo Last Supper in Milan, stand in awe of the great European Cathedrals, and attend concert performances of what were frequently intended to be liturgical pieces. During times of national tragedies like the post 9/11 period in New York, dozens of Requiem performances representing the work of numerous composers were presented while contemporary composers created new works on ancient texts. Somehow, no matter what your background, the experience of art can transcend its original intention. So do legends. My charge is to examine the text, history, and the archeology of legends. Out of that, if you are lucky, will emerge each composer’s reaction to all of these things.

I have never heard a bland setting of the Regina Caeli, and Guerreo’s setting is certainly anything but. During the Renaissance, eight-voice polyphonic composition was considered the ultimate musical achievement, especially eight non-antiphonal voices. Despite the source and most modern editions trying to force this piece into two separate choirs, it just isn’t. On one of the rare occasions, you hear two four-voice choirs in what appears to be an antiphonal section is in the Alleluias toward the end. But, Guerrero tricks us. The antiphonal choirs are constructed from thusly: S2, T2, A1, B1, and then S1, T1, A2, B2. What you actually experience is a vivid array of intricately moving lines tightly stitched together in a multi-hued tapestry of sound. There are many settings of this antiphon that I love, but I think Guerrero’s is my favorite.

The last question is, did it work? Is the sword well and truly sheathed? Will we be able to resume our in-person season? I think so. New Yorkers are an intrepid bunch, and I think once the majority of us are vaccinated, we can return to our performance spaces and our love of ensemble singing. So stay tuned; Polyhymnia will be back. In the immediate future, we are going to dip our toes in the water with a YouTube recording and premiere. We will be singing selections from Palestrina’s 1584 Song of Songs collection.

While the Music in Isolation series has been what we needed to do, it doesn’t replace the joy of making music together in the same room. We have done a pretty good job of recording much of what would have been on our 25th Anniversary concert in May of 2020, it will still be our 25th season, if not our 25th year, when we return to live performance and we will celebrate accordingly. As the people of Rome did as the plague retreated, we will return to our daily lives, though probably not unchanged. We have survived a pandemic that has revealed the vulnerability of the human race and the inequities in our divided society regarding access to treatments and medical care. I hope we don’t forget what we have learned and take it with us to prepare for the next one, and yes, there will be a next one.

But in the short term, let the next roaring 20s begin, and as John Wesley the great writer of English hymns said: “Sing lustily and with good courage.”

Leave A Comment