Polyhymnia’s choice for Lent and Holy Week for our Music in Isolation series, recently posted, is Inter vestibulum et altare by Christóbal de Morales (c. 1500-1553). When I discovered this, my thoughts wandered to my first concert with Polyhymnia in the fall of 2015; Morales was the featured composer for that concert.

Joining any choir group is always a stressful process. I have endured this experience over many years with choirs covering the full gamut of sizes, genres, age ranges and ability. Nowadays when I have leadership roles with choirs, I try to use that experience to help them when recruiting. I think of the process as a series of hurdles.

The easiest hurdle is the technical one of finding people to come to auditions. The advertisement should be well designed and cleverly placed, and be welcoming as well as informative. In New York this is very easy because we have such a large market, and the wonderful www.van.org website as a resource. In 2015, as soon as I had agreed with my wife that there was space in my calendar for another group, preferably an early music group rehearsing on a Wednesday, finding Polyhymnia as an option was very simple.

The next hurdle takes singers as far as their first rehearsal. In business, I came to realize that interviews were often more random than picking names out of a hat, and auditions are frequently scarcely more discerning. Everybody is nervous, and often none of the parties are very clear about what they actually want.

I find the part that choirs usually mismanage is persuading people to continue after attending one or two rehearsals. An audition shreds the nerves, but a first rehearsal can be worse. Pitfalls lurk everywhere. The new member arrives early and has the misfortune to choose a seat that the doyenne of the sopranos has occupied since the previous century. Fixed smiles of welcome conceal nosiness, the beginnings of rivalry or premature judgment.

It is here that a common choir curse starts to kick in. The new member senses that every criticism by the conductor is targeted at her alone. He interprets every sotto voceside conversation by neighbors as ridiculing his incompetence. She feels intimidated when everybody else seems to read the music much better than her, forgetting that some had the music in advance or performed it only a year ago. Singers seem way above his league, because the ones he notices are the loudest and most confident rather than the timid ones struggling like he is.

Too often I have ended up discussing with other choir leaders how a precious new recruit who seemed so promising showed up for one or two rehearsals and was never seen again. This curse is easy to fix if we remember how we were once this petrified soul. We should always try to approach new members of our groups after their first rehearsals to offer a personal welcome, compliments and encouragement.

In my case, there is often a reverse side to this curse. I spend one semester feeling inadequate, overmatched and self-conscious. Then I hit a sweet spot, but this only lasts a few weeks. After that, I become complacent and judging. The criticisms of the conductor, so recently daggers to my own heart, seem no longer relevant to me but directed at him, and her, and her, and him. I become lazy, and everybody’s experience is diminished as a result.

Polyhymnia is not immune to these tendencies, but luckily the curse reared its ugly head to a lesser extent. The sweet spot came very quickly, and still remains after more than five years. Polyhymnia manages the integration process well, at least for me.

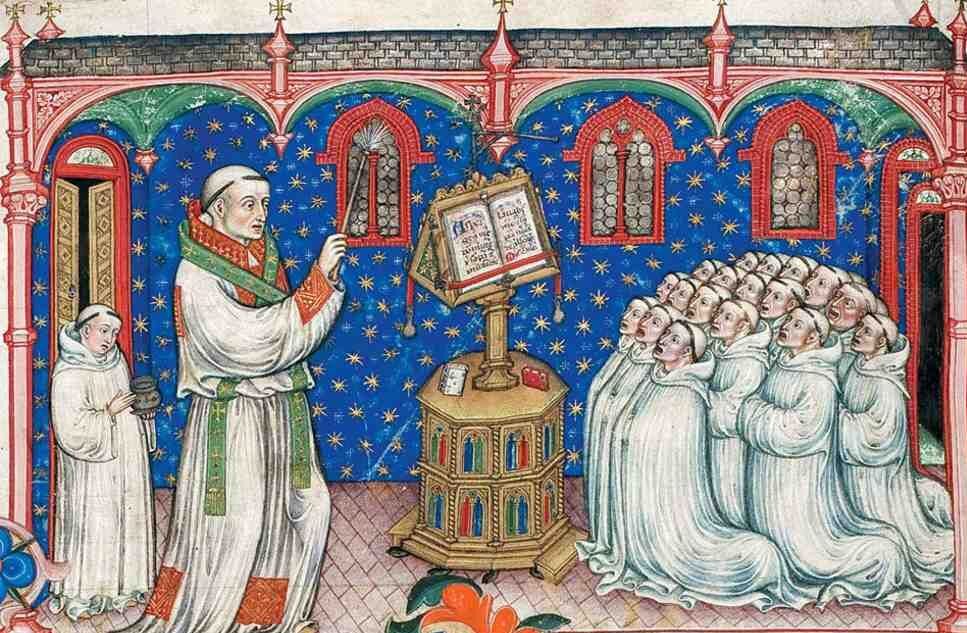

This started at the audition. I arrived and was immediately handed a heavy brick of Morales sheet music and invited to sing with the group for the night. It was the first rehearsal of the semester so everybody else received the same brick of music. We started to sing, and I couldn’t believe how we just sang and sang. A Gloria or Credo might be eight minutes long, but the group sang it right through and enjoyed it. Then John Bradley made a couple of remarks and we sang it again. Most groups can’t get past twelve measures before a collapse or the conductor feeling the need to hear his own voice. Not so Polyhymnia.

Singing with the group is an especially smart way to audition for early music. The goal in this type of music is generally to blend, to be hidden within the texture rather than proudly declaiming ones own line. Luckily the method suited my strengths. As a mathematician brought up in the British choral tradition, I have always been blessed with strong reading skills. It helped that we were singing Morales, with tough intervals at times but always melodic and expressive and rarely rhythmically obscure.

Even with Polyhymnia, I was not immune to the curse. In the Morales season, I remember how my line often seemed to provide the major third in cadences. Placing this in tune is never simple, and I regularly felt exposed, especially when we were asked to hold the chord and John’s body language betrayed dissatisfaction. The way to fix the problem is to focus on a confident and supported sound, but of course while under the curse we are more likely to become tentative and try to place the note carefully, which rarely works.

The music in that first Morales concert was a joy and he remains one of my favorite composers. The Lenten motet we are presently preparing is also delightful. There is something special about the Spanish renaissance. For me, it has the same perfect composition as Italian renaissance music but it adds some welcome spice. Well-written Spanish pieces contain more surprises, more raw emotion and more edge.

One way to express this difference is to compare Chianti with Rioja. Fine Chianti is perfect in every way, but a good Rioja can engage the emotions more deeply. There is something raw about it, and if I am in the mood to really drink, a Rioja is my first choice.

I hope I can illustrate with an example from the Morales motet. At the emotional high point of the piece, Parce, parce Domine populo tuo (Spare, spare your people, Lord), Morales sets a strong root via a B flat entry in the bass followed by a high F entry by the tenors. The bass then moves to an A natural before a tenor E natural. Most E’s earlier in the motet have been flattened to create a gentler effect, and this E natural is jarring: while not a tritone, the strong B flat root makes it feel like one. The emotional effect is powerful.

I looked up another Spanish renaissance favorite, Pater Dimittis Illis, and discovered that Vivanco uses precisely the same motif at his emotional highpoint of Deus meus, ut quid derelinquisti me (My God, why have you forsaken me?). The passages are eerily similar. Is this an example of early plagiarism? I prefer to attribute it to the shared Spanish soil and Spanish soul, and perhaps to a shared taste in Rioja.

Leave A Comment