When we were asked to pick a motet we loved to write about, I was stumped. To be honest, almost everything we sing in choir becomes something of a favorite. It usually doesn’t start that way, but I always enjoy it by the end of the rehearsal period—whether it’s a piece that I love at first sing, or whether it’s a piece that’s taken a lot of work to get concert-ready. There are certainly pieces that make me nervous—whether it’s because of a difficult, exposed entrance, or because it demands an endless breath-free phrase (my greatest singing challenge), or goes higher or lower than usual.

I admit that the last experience is one of my favorite experiences as an alto, though. I love when we mix it up with the tenors in their range, or with the sopranos (second sopranos, obviously, since I’m never going to get as high as the sopranos do at the top of their range.) As an alto for so many years, I do enjoy a brief stint as the melody sometimes, but what I love the most is being in the middle of the mix of voices, bouncing off one part and then another.

Maybe that’s what made me pick In Illo Tempore as one of my many favorite motets. As our conductor, John Bradley, wrote in the program, “Gombert remains one of the great masters of the early Renaissance, deploying vocal lines and wielding oceans of rich, dense and occasionally dissonant polyphony.” There is no better feeling than being in an ocean of polyphony.

If you’ll join me, I’d like to introduce you to some of my favorite alto moments of In Illo Tempore. I’d recommend listening to it a little too loudly using headphones. It’s the best. (The Soundcloud link to our performance of In Illo Tempore can be found below.)

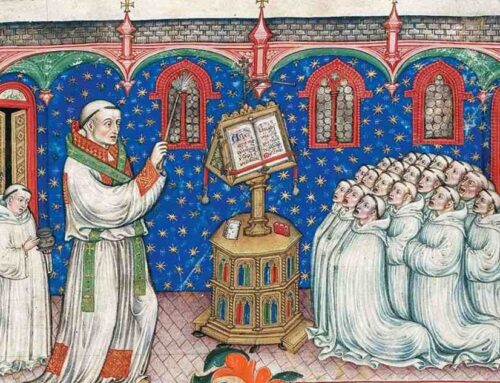

In Illo Tempore is in 6 parts, and we altos sing the second-highest line. You might have trouble following it, since the tenors and altos in this piece weave in and around each other, with the altos frequently going under the tenors and near the bottom of our range. The weaving starts immediately, with us beginning the story: In illo tempore (“At that time…” in English) and that’s certainly how I feel-like we’re storytellers. The score we used has a note that says, “unhurried,” which is much more an instruction for the lower voices, who keep steady while the altos and sopranos mix it up with faster and syncopated notes. John says it better than I ever could: “Gombert employed ‘pervasive imitation’ in which motific figures appear through all of the parts simultaneously…”

As a singer, it is SO FUN. I will also admit fully that the first alto line, which I also had to mark “breathe high” is really tough. It starts relatively low, well below my break, then moves quickly up the scale, just keeps going, and HAS to line up perfectly with the sopranos once they start moving. This is one of the challenges with Gombert—keeping held notes alive, but being prepared to begin moving quickly after held notes, and then just singing and singing. There’s no hanging around in this piece (except by the first basses, who have to wait until measure 7 to come in!) The piece begins sparely, almost like it’s not going to be all that interesting (let’s be honest), and then you realize that all 6 voices have snuck their way in and it’s glorious.

The best place to hear that “pervasive imitation” that John referred to in his notes, is when we get to the next section, “loquente Jesu.” That theme comes in again and again, and the experience of singing together is so absorbing and joyful. You almost don’t realize that we’ve moved on to a new phrase until you hear that Gombert’s snuck a new phrase in the tenor line under the rest of the choir that the other parts imitate after the tenors. In the altos, we literally sing the same notes as the tenors—I often end up making eye contact with them as they hand it off to us.

As we head into the “extollens” section, the same imitation happens again, but the texture changes. The altos head to the bottom of our range, and pairs of singers then come in to sing “extollens”, which adds more weight and “insistence”, as the score says. For the next two sections, the altos emerge directly from another line.

The amazing thing about Gombert for a singer is that the music is just relentless—there is no pause, no cadence, no brief opportunity for a reset. So it’s our responsibility to create a different flavor for each section—drawing hints from notes in the edition of the music we used: “magisterial,” “a little more emphatic,” “authoritative, yet benign,” for example. The suggestions from the editor helped, since when you listen carefully, it’s not the same voice every time that begins a new phrase and idea.

In the middle sections of the piece, figuring out how to bring out the new words with a new tone or feeling was probably the hardest thing—the work of melding and separating from parts around us is much of the focus. Then, near the end, there’s “Quinimo…”, in which we bring up the intensity and obvious repetition again—most clearly at the beginning of the section.

At the end, we have two pages of the same phrase, over and over, which we’re asked to sing with “quiet conviction.” I love ending a piece this way—getting quieter and quieter—because we have to listen even harder to each other, and our dotted rhythms are in imitation of each other and we have to be lined up as carefully as we can. It may seem strange to end such a rich-sounding piece so quietly, but it’s really wonderful for a singer. The intensity of Gombert seems perfect for times when you need to be surrounded by sound and swept along—enjoy!

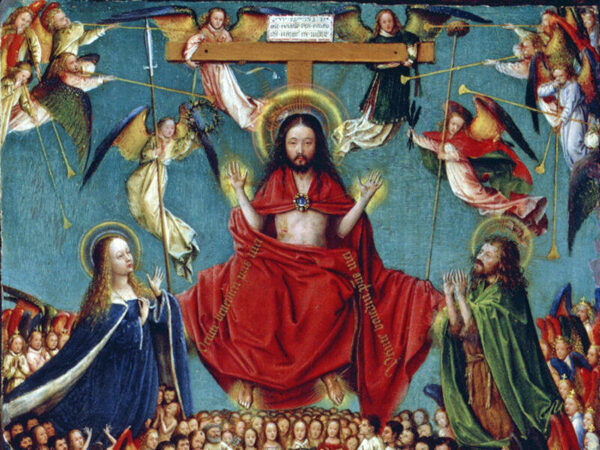

In illo tempore; Loquente Jesu ad turbas

Extollens vocem quaedam mulier de turba dixit:

Beatus venter, qui te portavit,

Et ubera, quae suxisti.

At ille dixit: Quinimo beati,

Qui audiunt verbum Dei, et custodiunt illud.

At that time, while Jesus was speaking to the crowds,

A certain woman from the crowd raising her voice said:

Blessed is the womb that bore thee

And the breasts that thou hast sucked.

But he said: Nay, rather, blessed are those

who hear the word of God and keep it.

Leave A Comment