I never got to meet my maternal great grandmother “Ma-Ma-Ma” (Rahela Jelinek, née Poljokan) but she lives on as a fascinating and colorful figure in my imagination. A Sephardic Jew from former Yugoslavia, she studied opera at the Vienna Conservatory and immigrated to the U.S. in 1925 to attend Juilliard on scholarship. The New York Times reviewed her 1943 Town Hall debut, giving special praise to her interpretation of Bellini’s bel-canto aria “Casta Diva.” (Apparently Ma-Ma-Ma could carry some “diva” qualities back home with her from the concert hall; I’ve heard stories about “Pa-Pa-Pa” having to dodge the occasional shoe that was lobbed at him in a heated moment).

Ma-Ma-Ma passed some of her musicality down to me and my two younger siblings. I became a professional pianist and musicologist; my baby brother excelled at percussion and now plays drums in a couple of local bands on the thrash metal spectrum; and, in an eerie case of possible reincarnation, my sister emerged from the womb a fully-formed dramatic coloratura soprano. I’ve been listening to her high notes since 1988!

While you could say that opera is in my blood, it’s not really in my body. I’ve always loved to sing, and took voice lessons starting from a young age, but due to certain physiological realities, no amount of classical training could make me sound like Ma-Ma-Ma or my sister. In truth, most people aren’t physically built to be operatic singers. Projecting over a full orchestra to a house of thousands requires that one be “a human bell, ringing in every hollow and bone” (Burkhard Bilger, The New Yorker). I am less of a booming bell and more of a narrow-ribbed individual with an oral cavity so petite that my dentist still has to use pediatric implements on me (seriously). When I was growing up, various choral directors and teachers described my singing voice in terms like “light,” “flutey,” “small,” “delicate,” “boy-soprano-ish.” I never developed a full-fledged inferiority complex about the glass-shattering musical-theater and proto-operatic voices that I heard in some of my peers, but sometimes I wondered if I’d ever find a niche for my particular timbre.

I can’t remember exactly when the concept of “early music” and “early music performance practice” entered my consciousness, but at some point in my teens I came into possession of a CD of the Tallis Scholars singing Palestrina’s “Missa Assumpta est Maria.” The sound-world enchanted me immediately: the polyphony was grand and architectural, yet I could simultaneously hear each individual line, each onset of a new word. Of course, much of this was due to Palestrina’s near-unparalleled ability to balance complexity and clarity, but the performers’ stylistic choices absolutely enhanced the effect. “I want to sing this music!” I remember thinking. “I bet my voice type would work with music like this.”

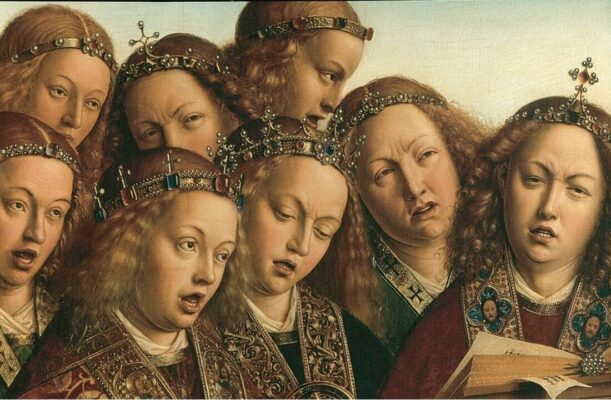

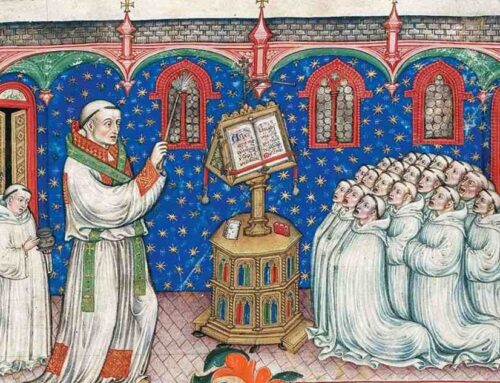

We can never know exactly how vocal ensembles actually sounded in the Renaissance. Still, conductors, performers, and scholars can make educated guesses based on evidence from iconography, treatises on musical style, written accounts of performances, and the acoustical properties of venues where pieces were first performed. A vague consensus of what early music singing “should” sound like began to emerge in the 20th century, and in large part this performance practice emerged as a conscious differentiation from a predominant “operatic” model of classical singing (vibrato-heavy, full-bodied, projecting to the nosebleed seats). This new early-music sound was lighter and leaner, flexible, judicious with vibrato and sometimes eschewing it altogether for a “straight tone.” Vibrato, the process of rapidly oscillating around a core frequency, lends warmth, richness, and individual color to sound, but can ultimately obscure the fundamental pitch. Choral music that is densely contrapuntal– i.e., most Renaissance and Baroque music– needs no extra interference from coloristic pitch manipulation, especially in unaccompanied repertoire where good intonation relies on purity of intervals. Add a hyper-resonant performance venue like a cathedral to the equation, and you definitely want your singers to produce as clean and focused a sound as possible.

To return to Palestrina, consider this gorgeous double-choir motet, “Surge, illuminare, Jerusalem” (1575), which I got to perform with Polyhymnia in 2018. See the link below for a recording of that performance. The first word, “surge,” means “arise,” and Palestrina sets it evocatively with a nimble ascending figure that passes among the four divisi of Choir I. The quicksilver precision of the polyphony would be utterly muddied if singers applied a hefty dose of vibrato, but the “early music” vocal paradigm makes the opening passage shine.

Back to my personal narrative: so, as a teenager I became obsessed with the sonic world of Renaissance and Baroque singing, and thought my voice might have something to offer the repertoire. I went away to Indiana University’s music school to study piano, but took advantage of the HIP (Historically Informed Performance) department and signed up for early music voice lessons as an elective. I had the opportunity to learn Dowland lute songs, Purcell recitative, French Baroque arias, Italian monody– all fascinating, challenging, and deeply idiosyncratic styles. During my Master’s degree I even took a full year of coursework on the analysis and performance of Bach cantatas. (I won’t get into all of the virulent performance-practice debates amongst Bach scholars, but I’ll just say that I came to love–and prefer–the pared-down sound of ensembles with one or two singers on a part). I moved to New York in 2011 to begin a musicology PhD; a friend that I made in the program (alto Naomi) sang with Polyhymnia and recommended the group to me. I officially joined as a soprano in 2017 after subbing on and off for a few seasons. There is no repertoire that I feel more at home singing than what John programs, and I feel privileged to be part of an elite ensemble where every member really “gets” the early music aesthetic.

My sister (Ma-Ma-Ma’s second coming) and I were catching up recently. Her operatic career is starting to pick up steam; she can toss off Zerbinetta like it’s nothing, and is learning Lucia di Lamermoor. We were commiserating about how COVID had flatlined our respective performance schedules for the foreseeable future, and I mentioned how I especially missed singing with my Renaissance ensemble. “Oh, I love early music and Renaissance polyphony,” she said. “I used to be in this madrigal group back at Eastman, just for fun. I wish I could sing that kind of stuff all the time, like, professionally.” Then she sighed. “But yeah, my voice just isn’t right for it.”

Leave A Comment