Qui tantus primo Parsone in flore fuisti,

Quantus in autumno in morere fores.

Parsons, you who were so great in the springtime of life,

How great you would have been in the autumn, had not death intervened.

John Dow

Robert Parson’s Ave Maria has always been very special to me. It was one of the first Renaissance motets I sang in a church choir and performed by Polyhymnia numerous times over our 25 years. I also can’t get through the Amen, either singing or conducting, without getting a little teary. The upheavals of the 16th Century were followed in the mid-17th Century by the Civil War and Interregnum. Another wave of religious zealotry further eradicated what little then remained of the medieval Church, not just music, but textiles, painting, and stained glass as well. The Eton Choirbook survived by chance, and only recently, a piece by Tallis was found plastered in a wall. The Reformers, especially during the reign of Edward VI, did what they could to erase the influence of the Roman Catholic Church. Cromwell and his cabal did all they could to erase the monarchy from history. But the Ave Maria survived. Though unsuccessful in the end, the damage had been done, leaving just a fraction of what had been.

Interestingly, I think this is what draws me to this repertoire. There have been some critical successes bringing the lesser-known Tudors composers and their music to a broader audience. The resurgence of interest and performance of music by John Sheppard and Nicholas Ludford are two happy examples. Sadly, while familiar to musicians in church music circles, particularly Anglican Church music circles, many of these resources still elude those in the wider choral community. There are some extensive resources such as Musica Britannica, Early English Church Music, The Oxford Book of Tudor Anthems, to name a few. Even so, even in the Oxford book, Robert Parsons is only represented by this single piece. Make no mistake, it is a wonderful motet, but there is always more to the story.

Robert Parsons is one of many Tudor composers about whom we know very little. I am again drawn back to England with an almost insatiable curiosity about composers whose backgrounds are shrouded in mystery. We are left with the nearly insurmountable task of sifting through the fragmented remains of institutional records to find, often in a very oblique way, a small morsel of information about these lesser-known composers. If we are very fortunate, we might uncover a little bit of insight into not only how they worked, and for whom, but how they lived. More often than not, we are left only with a small but inarguably well-crafted body of work and little else. One-hit wonders are more common than not, Eton Choirbook contributor John Sutton comes to mind. We know they must have composed more, but time, history, and even a lack of interest have taken their toll.

Robert Parsons, a generation younger than Tallis, is believed to have been born around 1535. Payments to him from the Chapel Royal from 1560 on suggest that he was master of the Children before his formal appointment as Gentleman in 1563. He drowned tragically in the River Trent in 1572. William Byrd succeeded him after his death. He has left a small but very significant legacy of rich mid-Tudor style music, as his fine setting of Ave Maria attests. His music is rife with rich harmonic textures and extensive passing, and suspended dissonance. Whether he was a recusant Catholic or not remains to be seen; some have suggested that the Ave Maria, which dates from around 1568 -1570, might be a nod to Mary Queen of Scots. There is no direct evidence to support this interesting, if somewhat romantic theory. He was also an eloquent composer of canticles for the Reformed Anglican services of Mattins and Evensong for Elizabeth I. Parsons’ First Service is a masterpiece.

Parson’s Ave Maria has been beloved of choirs in both the Anglican and Catholic traditions since it was published in the much-revered Oxford Book of Tudor Anthems in 1978. Settings of the Ave Maria are unusual in England, and even Byrd’s attempt is somewhat pedestrian, seemingly composed as a requirement to fill out the liturgical requirements in Gradualia. Parsons’ offering is sublime. The treble part, much of it written in long, soaring notes, is not as it might seem at first glance a cantus firmus, but rather a freely composed musical fan vault beneath which the more intricately wrought lower parts swirl and echo. Parsons shifts from grandeur to poignancy at et benedictus, leading the motet to its glorious conclusion with a particularly English setting of Amen, which may very well be the most beautiful and heart-wrenching setting of that word in Renaissance music. Parsons’ setting does not include the invocation for the dead, Sancte Maria, ora pro nobis… “Holy Mary, pray for us…” which wasn’t officially added by the Roman Church until 1568. Elizabeth I not only tolerated Latin in her private chapel but encouraged it. The motet is at the same time sad and celebratory, offering a glimpse of what might have been possible should Parsons not have met his untimely death, an immeasurable loss to the nation and the Chapel Royal.

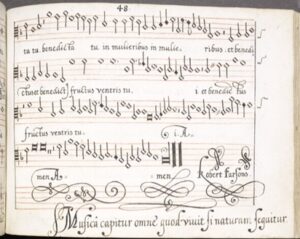

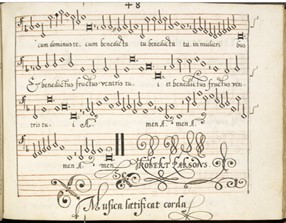

The music of Byrd and Tallis survived in no small part due to the monopoly given to them by Queen Elizabeth. Despite the unfortunate reality that the 1575 Cantioes Sacrae was less than a commercial success, the fact the collection was in print increased the chances that the works would survive. The other option was the personally assembled, hand-written anthologies, made for mostly personal use and privately owned. They escaped Cromwell’s institutional purges. The Forest-Heyther Partbooks, the Baldwin Partbooks, and the primary source for the Ave Maria, the Dow Partbooks the three best-known. The Dow Partbooks take their name from Robert Dow, who in the 1580s assembled one of the most comprehensive sources of Tudor music. The partbooks include sacred, secular, and instrumental compositions by some of England’s greatest composers and include a few continental surprises such as two motets by Lassus. It was Robert Dow himself who copied the Ave Maria. His hand was incredibly steady, and the clarity of the notation makes them an invaluable tool for copying music into modern editions.

The images above are the second page of the medius and bassus part of Ave Maria from the Dow Partbooks and include both the beautiful calligraphic rendering of Parsons’ name and two interesting Latin quotes, which are:

Musica capitur omne quod vivit si naturam sequitur

Everything that lives is captivated by music if it follows nature

and

Musica lætificat corda

Music rejoiceth hearts

Leave A Comment