How the discovery of one composer and half of a motet led to 25 years of concert material

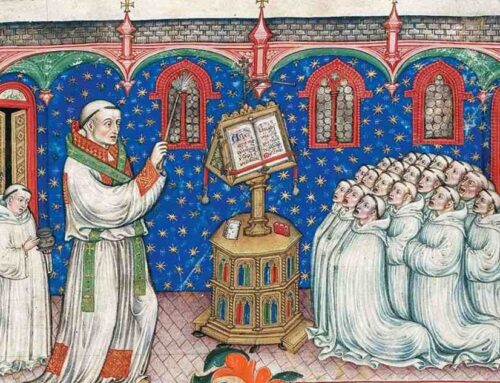

I am guessing that anyone who has ever sung in a church choir has run into the Chester Motet Books. In the years before music editing programs became the go-to for transposing music from original clefs and keys into settings which prevented choral singers from meeting the director after rehearsal with torches and pitchforks, the Chester books were there with singable editions of classic motets. Years ago, Polyhymnia used to present an annual candle-light Christmas concert in which we, through music, told the story of the nativity. The musical choices extended from the Prophecy to the Epiphany. There is a wealth of material for Advent and Christmastide, and between Chester and both versions of the Oxford Book of Carols, we had several years of popular Christmas concerts. On the very first concert was a truly magical piece of music by a composer that the inexperienced me hadn’t run across yet, Jacobus Clemens non Papa (c.1510-1555/6). My graduate school collegium had given me the chance to perform a wonderfully broad array of Renaissance composers, but for some reason, during the three years I was there, no Clemens. But anyway there he was, and the motet was Magi veniunt. I was now completely enamored of this composer with the unusual sobriquet.

So I started to dig deeper. Along the way, I discovered a lot of things. Magi, as published in the Chester anthology, was just the first part of a two-part piece, which, when performed as a set, really reaveals the eloquent musical balance of the motet. Although I was interested in Music History and Musicology during my college and graduate school years, I was mostly concentrating on performing. Then, once in New York, and left to my own devices, the obsession for digging through dusty basements and looking at Microfilm (quaint I know) got me. I became an annoying regular at the New York Public Library trying to get around their photocopying restrictions, I sneaked around security guards into the Music Library at Columbia University, and finally joined the Verdi Society (Yes, I know), which for a time was the way into the NYU library. Once employed by NYU and I was granted borrowing privileges, the keys to the kingdom were mine!

Magi veniunt, published posthumously by Pierre Phalèse in 1559, is a masterfully constructed, episodic account of the visitation of the Magi. Though he uses texts from office responds for both sections, neither is in the correct form, suggesting an extra-liturgical use. Both parts begin with a line of narration followed by words spoken in the voices of the Magi themselves. It is a dramatic, atmospheric composition, with an underlying sense of stateliness that evokes the feeling of a regal procession through the wilderness. Particularly eloquent, is the way the text deployed majestically at Rex Judaeorum contrasting with a sense of wonder at cuius stellam vidimus. In the second section, the musical punctuation of aurum, thus et myrrham—gold, frankincense, and myrrh on long sustained notes is particularly dramatic. It portrays the moment the Magi present the traditional gifts to the infant Christ. The motet concludes with an initially elaborate Alleluia, which illustrating their departure, tapers off into the twilight, ending quite remarkably on an open fourth.

Magi veniunt was my way into the rest of Clemens’ body of work, leading to my edition of his Missa Pastores quidnam vidistis, which in turn led me to the sumptuous seven-voice Ego flos campi. That motet led me to Jacob Vaet, student of Clemens and Kapellmeister to Maximilian I, who composed a mass on Ego Flos campi, to the friendship between Vaet and Maximilian I, and their close relationship with the Bavarian court, Albrecht IV and his choirmaster, Lassus. By then, I was hooked on the Habsburgs. There was no going back. I had a taste of Maximilian I at an Amherst Early Music Festival several years before where we created a pretty good CD of music of Heinrich Isaac. I connected Clemens to Charles V, and that opened the door to some other really great composers, Crequillon, Gombert, Manchicourt, even turning back around and rediscovering Victoria twenty or so years later. Victoria, the most famous Spanish composer composed his Requiem for a Habsburg princess.

Magi venienut ab oriente Jerosolimam quaerentes et dicentes. “Ubi est qui natus est Rex Judaorum cuius stellam vidimus et venimus cum muneribus adorare Dominum.”|

Magi videntes stellam dixerunt ad invicem: “Hoc signum magni regis est eamus et in quiramus eum et offeramus ei munera aurum, thus, et myrrham.” Allelluia.

The wisemen came from the east to Jerusalem inquiring and saying, “Where is he that is born King of the Jews, whose star we have seen? We have come with gifts to offer the Lord.”

The wisemen, seeing the star, said to each other: “This is the sign of a great king. Let us go and ask after him and offer him gifts—gold, frankincense, and myrrh.” Alleluia.

Leave A Comment