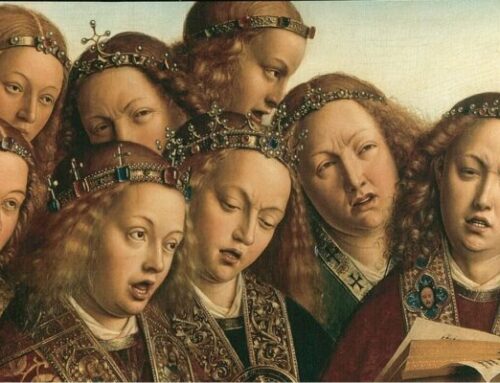

One of the last “normal” things I did before lockdown was sing in the dress rehearsal for a Polyhymnia concert that never was. The dress rehearsal took place on Wednesday, March 11. You might remember it as THAT Wednesday.

When I went into rehearsal at 7:30, it still seemed as though things were proceeding in the world as per usual. We would warm up, run through our whole concert program, go home. Friday would be my husband’s last day teaching before March break. Saturday night would be our concert. Sunday night, my husband and I would leave for our honeymoon in Australia!

When I emerged from rehearsal two hours later, at 9:30, it was apparent that nothing would be going according to plan from here on out. I took my phone out and found a slew of texts alerting me to all the developments I missed in those two hours: an NBA player tested positive for COVID-19 during a game; Tom Hanks tested positive for COVID-19 in Australia; Trump was suspending all travel from Europe.

Within 24 hours, all our plans had changed: Broadway and the Met Opera and even our Polyhymnia concert were all shut down; school closed a day early; and we bumped up our departure to Australia by two days, a move that made the difference between a shortened but still enjoyable honeymoon and no honeymoon at all.

We returned from Australia on March 21 to a New York that was completely different from anything either of us had ever experienced: empty streets, shut restaurants, endless sirens. As I began to settle in to the new normal, I finally found myself with a luxury I had been rather short on the last few years: extra time to practice.

At first, I spent my time practicing piano, my main instrument. I dug into a couple of Beethoven sonatas I’d long been trying to learn and abandoning when life got busy, and I even made some progress on Schumann’s Papillons. I missed singing, of course, but I’ve only ever been a choral singer – I haven’t had serious voice lessons and don’t have a wish list of solo repertoire the way I do for piano. What would I sing and what could I work on if I didn’t have a choir to sing with?

Long before lockdown, I’d been feeling like I had reached some kind of internal limit as to how far my vocal technique could progress on its own, without guidance from a teacher. I had idly contemplated someday taking voice lessons, but had never gotten so far as looking into teachers.

Lockdown presented the perfect opportunity: a grad school colleague, Alexis Rodda, had just returned from her Fulbright fellowship in Austria, and was willing to spend some time coaching me via Zoom.

Over the first few weeks of lessons, I had some earth-shattering revelations: I finally learned what exactly was the deal with that “soft palette” thing singers are always talking about, and began to differentiate between (and control) my chest and head voices. I suddenly found myself able to spend 20 or 30 minutes working on a simple two-minute lied. And with Alexis’s encouragement, I gradually began to gain some confidence in the sound of my own voice.

And then on May 15, I flew off my bike and shattered my left wrist.

It was the first time I had returned to Manhattan since March (to be precise, since the day after that last Polyhymnia rehearsal). Irony of ironies, I was biking to my doctor’s office, to get some shots that had been long postponed due to COVID-19. It all happened so fast: I went over a bumpy patch on the First Avenue bike path, just north of Houston, and felt something fall out of my rear basket. I tried to brake and pull over, to see what had happened, and the next thing I knew, I had flown off my bike, landed face down on the bike path, and my bike was on top of me.

I knew within minutes that my wrist was broken; I broke my right wrist as a child, and had subsequently injured myself in enough other stupid ways to know instinctively the difference in feeling between a broken bone and a sprain. But it took a few days for the severity of my injury to really set in: to learn that I had not only broken but, in fact, shattered the radius, close to the joint, in a particularly tricky spot; that I needed not just a cast, but surgery, within the next week.

The surgeon assured me that even though it was a difficult break, he would be able to fix it. What he didn’t tell me, at least not right away, was exactly how long it would take to heal, nor how long it would be until I could play piano again.

Although I had been enjoying singing before the accident, as one component of my musical activities, it was in the weeks after surgery that singing really saved me. I tried a few times to work on just the right hand of some piano pieces, figuring that I could use the time to work out a few challenging passages, or develop some trilling super skills, or finally master scales in thirds. But it made me so sad to play with only my right hand that I abandoned this plan after only a day or two.

Singing, it turns out, is one of those rare activities that requires you to use your whole body, and yet doesn’t mind too much if one isolated part of that body isn’t particularly functional. I didn’t feel like I was desperately missing something, as I was when I tried to play piano one-handed. It was enough for me to just to hear the sound of my own voice, even without any piano accompaniment. And I found plenty to work on, just focusing on my voice: fixing the intonation of one particular pitch; figuring out how to support my breath through one long phrase; and trying to control that ever-mysterious soft palette.

A little over a month after my bike accident, my cast came off. I slowly began to return to piano — literally slowly at first, struggling to play a simple scale at maybe half or less of my normal speed. It hurt my stiff fingers and hand to play for very long, but I knew the movement was good for me.

The first piece that I tried to play all the way through was the piano accompaniment to one of the songs I’ve been working on in my voice lessons, Roger Quilter’s “Fear No More the Heat o’ the Sun”. It was tough to get through, and I had to leave out a lot of octaves and chords in the left-hand part, but I did it. And while I was perfectly satisfied working on the vocal line without the accompaniment, it was so nice to hear what the accompaniment sounded like and to feel it under my fingers.

Since that first attempt to play through the Quilter song, my left hand has steadily improved. I can do scales nearly up to speed now, and octaves and arpeggios feel a little better each day (even if they still have a way to go before they feel completely natural). I even managed to find a piece in my repertoire that fits the particular needs of my left hand at the moment: Brahms’s Romance in F major (op. 118, no. 5). It complements the Quilter song (which is in F minor) particularly well, and I’ve been enjoying practicing both in the same session, working on my voice, and then working on my piano.

It seems pretty clear at this point in the pandemic that I will continue to work remotely at least for the rest of the year. Here’s hoping that all this extra time at home allows for many more enjoyable practice sessions working on both piano and voice as I continue to heal.

Leave A Comment